Mario Cimino, Regional Director of the Pennsylvania Resources Council’s East Office and Morton Borough’s Council President. (SOURCE: Pennsylvania Resources Council)

Upstream/Downstream spoke with Mario Cimino, Regional Director of the Pennsylvania Resources Center’s East Office, who was kind enough to share his experience working at the Pennsylvania Resources Council and explain some of the organization’s priorities and recent initiatives. Mario also spoke about his work with the Upstream Suburban Philadelphia Cluster, and what it’s like to be Morton Borough’s Council President.

How Did You Get Involved at the Pennsylvania Resources Council? What Brought You There?

A combination of academic, professional, and life experiences brought me to the Pennsylvania Resources Council (PRC). I did my undergraduate degree in Environmental Studies at Susquehanna University, which I’d like to recognize here as having the oldest Environmental Studies program in the country! Since then I’ve specialized in stormwater management in my professional career.

After I graduated I worked in Environmental Consulting for a few years, and then got involved with several political campaigns. From there I transitioned to working in non-profit organizations, and finally I ended up at PRC. Every step of the way, I’ve made sure to keep my concern for the environment—and stormwater management in particular—at the forefront of my decision-making.

What are Your Primary Interests or Concerns Regarding the Environment, and Especially Stormwater, in Southeastern Pennsylvania?

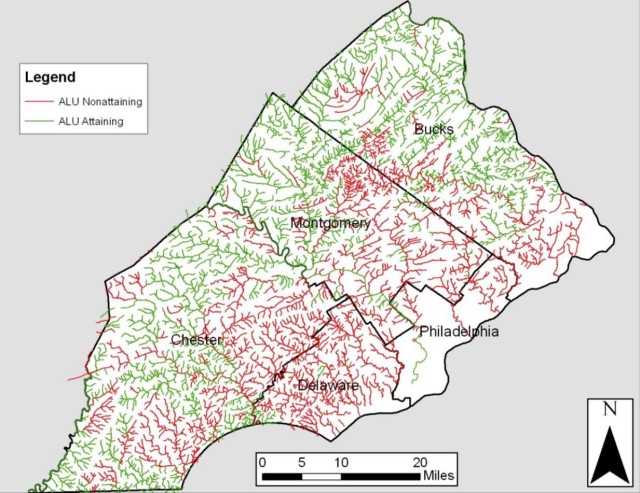

I view stormwater issues in Southeastern Pennsylvania through two main angles. First, there’s the fact that many of the environmental rules and regulations that come down from the Federal Government through the Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) are unfunded mandates that are hard for small, cash-strapped boroughs in the region to uphold. Second, but tied to the first issue, is the problem of educating the public about stormwater. It can be tough to get people excited about stormwater, especially when they can’t see the effects of environmental degradation in their local streams.

That said, the local level—counties and municipalities—has far more potential than the national or state level to make a positive impact on environmental issues relating to stormwater. Watershed health, for example, could be greatly increased by banding municipalities together to work on reducing pollution at the regional level.

However, the local level is chronically underfunded, and with the recent change in leadership at the US EPA it looks like federal funding for issues like stormwater management will dry up even more. I’m confident that organizations like the William Penn Foundation and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation will remain steady streams of funding for stormwater management issues in Southeastern Pennsylvania. That said, less federal funding for stormwater management in the future will result in fewer green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) projects in the region.

Costs for GSI projects and stormwater system upgrades are rising, and the local level is always the hardest hit by these increased price tags. In the 1970s, when municipalities across the country were struggling to deal with their aging sanitary sewers, the federal government released a substantial amount of money in cheap loans and block grants to municipalities to make these much-needed upgrades. Now, though, there is little similar funding available.

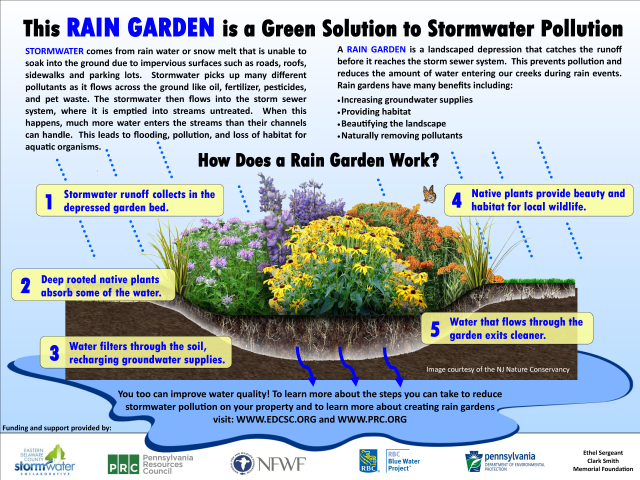

Ultimately, it comes down to educating the public. An informed public can reduce the financial strain on municipalities to meet federal environmental regulations, as the residential sector is one of the biggest contributors to stormwater management issues at the local level. Even things as simple as holding public workshops to teach homeowners how to install rain barrels on their property can make a huge difference.

Can You Explain a Bit About the Work That the Pennsylvania Resources Council Does in the Region? What Role Do You Play at the Pennsylvania Resources Council?

I am the Regional Director for the Pennsylvania Resources Council’s East Office (meaning Eastern Pennsylvania, there’s another PRC office in Western Pennsylvania). That means I run daily operations, manage project staff, manage the Environmental Living Demonstration Center in Ridley Creek State Park, and look for money and funding for PRC.

Due to my academic background in environmental studies and my work over the years in stormwater management, I also do a lot of work with various members of the Delaware River Watershed Initiative (DRWI), and I collaborate with local and regional stakeholders—including a broad cross section of government officials, businesses, and other organizations—to identify opportunities and share information on stormwater in Southeastern Pennsylvania. As a group, we work to educate the public through educational workshops, outreach events, and online through social media outlets.

Examples of this collaborative approach are the numerous GSI demonstration projects we are installing in high-visibility public locations, such as municipal buildings, around Southeastern Pennsylvania. These projects bring together municipal officials, residents, local businesses, and community organizations to spread the word about simple, inexpensive strategies for managing stormwater and improving water quality in our streams.

Example of a GSI project in front Yeadon Borough’s public library. (SOURCE: Mario Cimino, Pennsylvania Resources Council)

Does Any of PRC’s Work Overlap with the Goals and Initiatives of the Upstream Suburban Philadelphia Cluster (USPC) or Morton Borough? If It Does, How So?

I often have to be careful about which hat I’m wearing so that I don’t get my priorities as Regional Director of PRC’s East Office confused with my role in the USPC and Morton Borough’s Council President. I always recuse myself when conflicts of interest arise between the aims of my various positions, but I also try to ensure they work in tandem with each other.

For example, in my role at PRC, I often collaborate with DRWI on Darby/Cobbs Creek watershed initiatives. Also, since Morton Borough is in the Eastern Delaware Watershed I see firsthand how my work on water quality in Southeastern Pennsylvania is benefitting people at the local level in my own Borough and others around it.

As Morton Borough’s Council President, I’ve been trying for the past few years to drum up interest in stormwater so that, when I leave my role at the Borough, whoever takes my place carries on my legacy of dealing responsibly with stormwater issues.

Seeing watershed management issues from these varied perspectives offers me a unique vantage point. This vantage point has taught me that improving our environment provides important benefits to the health and quality of life in our communities, but that the cost of these improvements poses financial hardships as well. Typically, due to patterns of development in urban and suburban areas, communities with fewer financial resources tend to face greater environmental challenges. For this reason, it is neither feasible nor fair to expect the neediest communities to deal with environmental issues on their own. Equitable access to the resources such communities need can only come from broad-based support at the state and federal levels.

As an Elected Official, can you Speak About Some of the Challenges Facing Municipalities in Southeastern Pennsylvania Relating to Water Quality and Stormwater Management?

A big priority at DRWI, and at PRC as well, is educating the public about the importance of stormwater management to water quality. PRC’s mantra is that, by educating children about stormwater and water quality, they will educate their friends and parents and grow up to be stewards of their local streams and waterbodies.

One of PRC’s educational brochures on rain gardens. (SOURCE: Pennsylvania Resources Council)

PRC’s marquee public outreach and education program, which is aimed at children in public schools, is called “Stream Stewards.” Through this program, we get into local public schools and teach kids basic river biology and chemistry. To get the kids to connect what they’ve learned to the real world, we take them on field trips to local streams and have them look for some of the macroinvertebrates we taught them about in the classroom. Stream Stewards is a very popular program, and most of the kids we reach really seem to enjoy it!

Engaging the public in GSI upgrades is a major way to increase public knowledge about stormwater runoff and its impact on water quality. (SOURCE: Mario Cimino)

On a less positive note, the average person doesn’t know what a clean or a dirty stream looks like anymore. Since the 1970s and 1980s, we’ve done a great job in this country of getting rid of visible pollution, like illegal dumping and chemical spills, in our streams and rivers. While this is a good thing, it also makes it hard to get people excited about cleaning up their streams and rivers because, if they can’t see the pollution, why would they care about cleaning it up? For example, the Darby/Cobbs Creek watershed is much more polluted than the Ridley Creek watershed, but if you were to take the average person to a stream in each of these watersheds, they probably wouldn’t be able to tell you which was in better shape.

Teamwork makes the dream work. (SOURCE: Mario Cimino)

How Do You See Other Municipalities in the Region Dealing with these Issues?

One major way municipalities in Southeastern Pennsylvania are dealing with stormwater issues is through the (EDCSC). The Collaborative was started by six municipalities a few years back, but now it’s up to ten. The original six municipalities formed the EDCSC to get a jump on stormwater issues in their area before they got too bad, and figured it would be more economical to share the costs of stormwater upgrades, repairs, and GSI installations. Also, since water quality is a regional issue, they thought it made sense to attempt to deal with it regionally. The York County Stormwater Collaborative has worked well and had many positive effects on stormwater management in that area, and in my experience (as well as most scientists’), dealing with something like stormwater on an individual basis simply does not work.

On the flipside, other municipalities are burying their heads in the sand when it comes to managing stormwater. A lot of the current elected officials in the region are refusing to do anything about stormwater because they know that they won’t be in office by the time real problems crop up.

Can You Talk a Bit About Some of the Other Hats You Wear?

In addition to my three main roles, I also work with and volunteer for a few local organizations on stormwater and other issues of environmental concern, but my main side hobby is Historic Preservation. One of the main Historic Preservation efforts I’ve been involved with over the past year or so that I’d like to give a shout out to here is called “Save Marple Greenspace.”

The effort concerns the 213-acre Don Guanella forest, one of the last remaining shreds of “Penn’s Woods” in eastern Delaware County. Given the runaway development in Delaware County over the last 20 – 30 years and the county’s ranking as having one of the poorest air quality indexes of any county in the United States, saving the forest from development serves the dual role of providing much needed green space to local residents and as a buffer against doing further harm to the area’s air quality.

The land is currently owned by an Archdiocese that relies on local, county, and state taxpayers to cover some of their share of the bill. To circumvent what they saw as a burden on local taxpayers, Marple’s elected officials sought to broker a deal between the Archdiocese and a real estate company that wanted to overdevelop the land. So far, “Save Marple Greenspace” has successfully advocated for the area and development plans are off the table, but the land isn’t out of the woods yet. I look forward to continuing this fight and hope we’re successful in keeping the Archdiocese’s land safe from development!

The effort concerns the 213-acre Don Guanella forest, one of the last remaining shreds of “Penn’s Woods” in eastern Delaware County. Given the runaway development in Delaware County over the last 20 – 30 years and the county’s ranking as having one of the poorest air quality indexes of any county in the United States, saving the forest from development serves the dual role of providing much needed green space to local residents and as a buffer against doing further harm to the area’s air quality.

The land is currently owned by an Archdiocese that relies on local, county, and state taxpayers to cover some of their share of the bill. To circumvent what they saw as a burden on local taxpayers, Marple’s elected officials sought to broker a deal between the Archdiocese and a real estate company that wanted to overdevelop the land. So far, “Save Marple Greenspace” has successfully advocated for the area and development plans are off the table, but the land isn’t out of the woods yet. I look forward to continuing this fight and hope we’re successful in keeping the Archdiocese’s land safe from development!

Article by Zhenya Nalywayko, based on an interview with Mario Cimino. Photographs courtesy of Mario Cimino.